In the quiet corners of forests and meadows, an unsung hero of decomposition performs its vital work with neither fanfare nor recognition. The burying beetle, nature's undertaker, carries out one of the most ecologically crucial yet often overlooked tasks in the natural world. These remarkable insects have perfected the art of recycling death into life, transforming carcasses into sustenance for future generations while maintaining the delicate balance of ecosystems.

Burying beetles belong to the genus Nicrophorus, a group of about 75 species found throughout temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere. What sets these insects apart is their extraordinary behavior surrounding carcasses of small vertebrates. When a mouse or bird dies in the forest, these beetles can detect the corpse from up to two miles away using their highly sensitive antennae. Within hours, multiple beetles may converge on the body, beginning one of nature's most fascinating funerary processes.

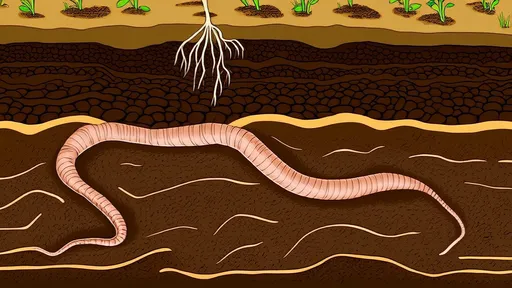

The beetles work with astonishing efficiency, coordinating their efforts to bury the carcass before it can attract competitors or begin to putrefy excessively. Using their strong legs and specialized flat bodies, they excavate soil beneath the corpse, gradually lowering it into the earth. A dead mouse that might take weeks to decompose on the surface can be completely interred in a matter of hours through the beetles' concerted labor. This rapid burial serves multiple purposes - it preserves the nutritional quality of the food source, hides it from other scavengers, and creates a protected environment for the beetles' offspring.

Perhaps most remarkable is the beetles' parental care, unusual among insects. After preparing the burial chamber, the beetles strip the carcass of fur or feathers and coat it with antimicrobial secretions that retard mold growth. The female then lays eggs in the surrounding soil. When the larvae hatch, both parents feed them regurgitated carrion, a behavior more commonly associated with birds than insects. In some species, the larvae even beg for food by stroking the parents' mandibles, triggering the feeding response.

The ecological importance of burying beetles cannot be overstated. By recycling carrion, they prevent the spread of disease and return nutrients to the soil more efficiently than natural decomposition would accomplish. Their activities enrich the forest floor, benefiting plants and microorganisms alike. Scientists estimate that a single pair of burying beetles can recycle the equivalent of a small mouse every week during their active season, making them crucial players in nutrient cycling.

Despite their ecological value, many burying beetle species face threats from habitat loss, pesticides, and light pollution. Several species are now endangered or threatened, particularly in areas with intensive agriculture. Conservation efforts have begun to focus on protecting these important insects, recognizing their role as ecosystem engineers. Some programs have established "beetle banks" - strips of undisturbed habitat where burying beetles and other beneficial insects can thrive amid agricultural landscapes.

The life cycle of burying beetles offers profound insights into nature's circular economy, where death fuels new life in an endless cycle of renewal. These unassuming insects demonstrate how even the most humble creatures play vital roles in maintaining the health of our planet. As we continue to unravel the complex web of ecological relationships, the burying beetle stands as a testament to nature's ingenuity - a tiny undertaker working quietly beneath our feet to keep the world clean and fertile for generations to come.

Beyond their ecological function, burying beetles have captured scientific interest for their complex behaviors. Researchers have documented elaborate courtship rituals, with males attracting females to carcasses through pheromones. The beetles can adjust their reproductive output based on carcass size, laying more eggs when resources are abundant. Some species even engage in cooperative breeding, with multiple females sharing a single large carcass and raising their young together.

The beetles' chemical defenses are equally fascinating. When threatened, they emit a foul-smelling secretion from abdominal glands that deters predators. This same secretion contributes to the preservation of their buried carcasses, inhibiting bacterial and fungal growth. Scientists are studying these antimicrobial properties for potential medical applications, particularly in an era of increasing antibiotic resistance.

Climate change presents new challenges for burying beetles. Rising temperatures may disrupt the delicate timing of their life cycles or alter the distribution of the small vertebrates they depend on. Some researchers suggest that warmer winters could benefit certain beetle species by extending their active season, while others warn that increased drought could make carcasses harder to bury in hardened soil. Understanding these dynamics will be crucial for predicting how decomposition ecosystems may shift in coming decades.

For indigenous cultures worldwide, burying beetles have often held spiritual significance. Some Native American traditions view them as symbols of transformation and renewal, while European folklore sometimes associated them with death omens. These cultural interpretations reflect humanity's long-standing observation of these insects' unique relationship with mortality, even before modern science understood their ecological importance.

Citizen science projects now engage the public in burying beetle conservation. Volunteers monitor populations, report sightings, and even create artificial burial sites to support local beetle colonies. These efforts not only gather valuable data but also raise awareness about the importance of decomposition in healthy ecosystems. As one participant noted, "After you've watched beetles carefully prepare a burial chamber and tend their young, you never look at a forest floor the same way again."

The story of burying beetles reminds us that nature's most essential processes often go unseen. While we marvel at charismatic megafauna and colorful blooms, these small custodians work diligently to clean and renew the earth. Their existence challenges us to reconsider our definitions of value and beauty in nature, suggesting that true importance may lie not in visibility but in function. In an age of environmental crisis, the humble burying beetle offers both a lesson in sustainability and a call to appreciate the intricate web of life that sustains us all.

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025

By /Jun 10, 2025